In a bid to initiate a relationship from the San Francisco Bay area with that of Shenzhen, China, the mayors of the respective bay areas signed an MOU officiating a cultural exchange relationship, recognized formally as a Friendship City in late 2024. Somehow, through the course of events at large and their inexplicable and continuous unfolding, this agreement and my own life intertwined. In late June I accompanied a crew of 16 promising teenagers to the Asiatic boom town of Shenzhen, China. I was able to witness firsthand the aftermath of an economic crossroads circa 1980 which resulted in astronomical growth exemplified in Shenzhen’s production sector. We explored facilities of industries such as BYD(a battery manufacturer turned car manufactory), a robotics company, a waste incinerator, a screen manufacturing company, and a genome sequencing lab, among a host of other parks and schools. I know perhaps more now about Deng Xiaoping’s designation of Shen Zhen’s status as China’s Special Economic Zone than I did about the Silicon Valley upon embarking on the trip, despite my proximity. The reflections I was able to garner from the experience filled gaps in myself understanding as a leftist American, a California artist, and a Bay Area (transplant) of central valley origin that inspired a working didactic journey to explore the history of U.S.-China relations.

Wearing the hair shirt of my verifiable left leaning politics and their associated monikers, with my visible piercings and tattoos, I wondered if I was the ideal candidate. I had never been to China, but it’s no secret that our relationship has been a contentious, albeit economically codependent one. I hadn’t taken it upon myself to do my due diligence in researching the region but knew enough at least to be suspicious of what I had been told. Still, I wasn’t sure what the rumors of stringent social norms would equate to in terms of me walking around playing the part of myself, a visibly verifiable ‘weirdo’, often saying exactly the thing I should not say through sheer lack of wit (regardless of where I am, I am told).

I pre-lamented to friends with modest bewilderment at my luck of being chosen. Surely the teenagers on this trip would be on a momentum of a different caliber than mine at their age, regarding the trajectory of their lives. Hailing from private schools and awaiting dorm assignments for places like Carnegie Mellon, I wasn’t sure I had much to offer them in terms of guidance and insight as a public school art teacher. I could no more explain a dividend than I could a terabyte, though I could give some insight into the auspicious symbols present in paintings from the Tang dynasty, should we see any. Nevertheless, as a warm body with a legal qualification to supervise, I would do just fine.

This identity crisis, though perhaps annoying to read about for some, was not entirely baseless. That’s not to say that every person I encountered on this trip was not exceedingly kind, welcoming and curious. The opposite of cold or judgmental, children called me beautiful (or once, to my delight, ‘comrade’), tour guides asked me questions about my life and my thoughts, college students exchanged WhatsApp numbers and offered to be pen pals. The people I encountered were endlessly graceful, inviting, and sweet; though in a conversation I had with a tour guide that had been with us throughout the trip, a young girl mentioned that she saw my earrings and tattoos and at first thought, “She looked like a bad person.” What I’m hitting upon here is the way that my identity was painted all over me, as clear as day, and how this outward expression of identity was antithetical to the norm for China. For better or for worse, artists who belong to the American left do not know subtlety. So far, we haven’t needed to. In fact, it’s these monikers that profligate interest in artists, their deviation from normal values, in the same way that we notice an oddly shaped squash. Their wares adorning the walls of high ceilinged lofts, artists are the purveyors of stock that exemplifies evidence of style.

How deep does this run? I’m thinking about American vernacular. While meaningless words like freedom are a bullhorn meant to drown out any deeper thinking here at home, I was finally able to visit China for comparison. A place that is constantly, obsessively and unscrupulously depicted as an oppressive one in my country. I am thinking about how hard history is to fully grasp, how censorship and propaganda does this (see: footnote). I am thinking about the value of what is left after purges of art, literature, and socially polite conversation. I am thinking about the goals of artists and their duty (without mentioning those that frustratingly and inexplicably do not believe that they have one). I am thinking about ‘the people’ and arts’ utility to them, and how in America, the beloved art of the proletariat is often a joke. I am thinking about how American artists would rather make something no one wants, or nothing at all, than make something that they do not wish to make. About what makes something precious, or daring, or true, and that even though nothing is true enough to be worth 14 million dollars, we obviously believe that art contains magic. I am thinking about how classism creates a religious regard for art, but how capitalism guts art of its romance. I am thinking about binary thinking, and the impossibility of making any worthwhile art within it.

Popular art among the proletariat, seen at Dafen Painting Village

Footnote: I should say that propaganda has become somewhat of a dirty word, and when I use it here I mean to say only that it serves a purpose and is selected specifically to do so. I understand that propaganda is used heavily all over the world by all governments, and basically any interpretive imagery used by any group seeking to wield or establish power on a population is by definition, propaganda.

I : MATERIAL SUPPORT, OR BULLHORN: CHOOSE YOUR WEAPON

Whereas loyalty to the party equates to material rewards in one place, why choose patriotism in another?

Artists that I share my life with often dolefully recount the ways we struggle to make a living. It can be part and parcel of the pioneer story of the artist that imbues one’s work with the legendary stuff we uphold as a testament to its value. Firstly, I think it’s important to note that American artists are unbridled by any parlance of visual tradition imbued by our short history, but instead, constant adaptability and an inexplicable proclivity towards breaking the rules skillfully. We are, after all, the birthplace of jazz. Secondly, our system of capitalism runs on the exploitation of labor by entrepreneurs. This is indispensable to understanding the nature of success for artists in America, and the obsession with artist celebrity.

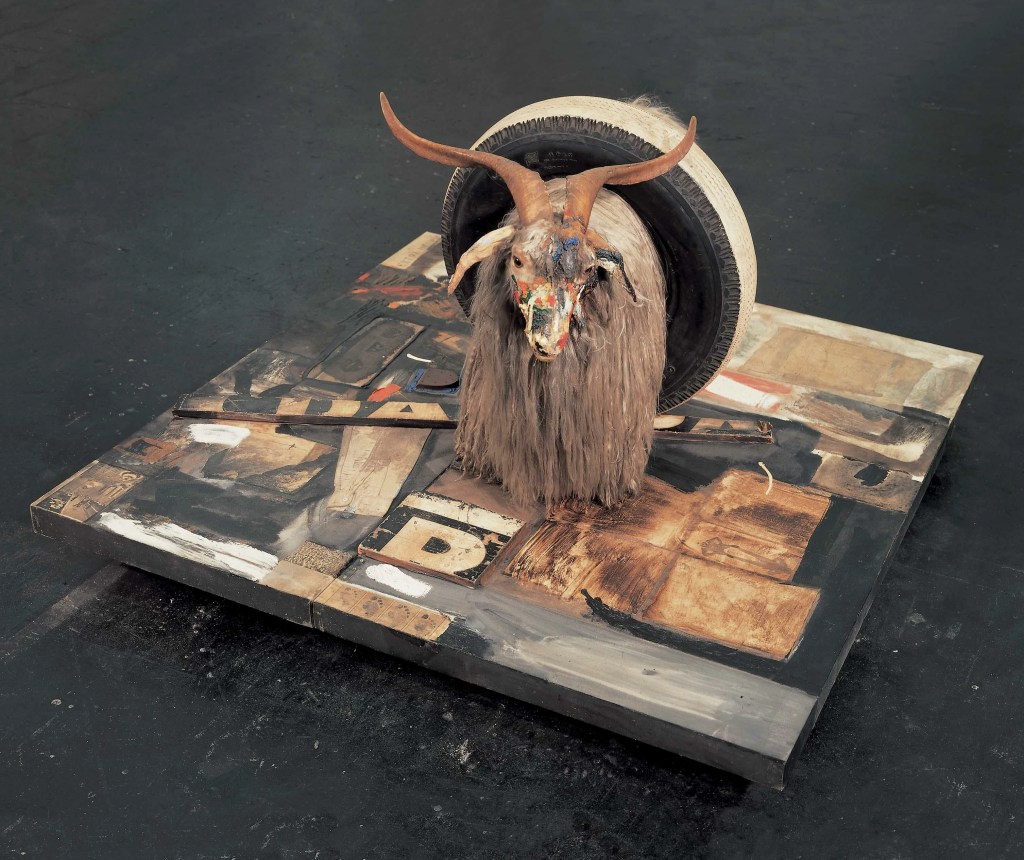

Unlike China, with 4,000 years of dynastic rule, cultural tradition, and comparatively undisrupted epigenetic history, the U.S. as a political entity is young. While artists in China take old symbols and reinvent them, in the west we work from scratch. Within a settler colonial nation that propagandizes itself as a bastion of free speech, artists build the foundation of their wares on upending this propaganda, all the while offering no solutions. Then they wait in the wings as the rich battle with paddles for who can spend the most money on it, the more controversial, the higher the price tag. Looking at Chinese scroll paintings is a Where’s Waldo of auspicious symbols and emperor’s seals, while American art can be whatever pretty trash Robert Rauschenberg took a shine to at the dump circa 1945.

The existence of Dafen Oil Painting Village may be an important indicator of how the arts are supported in places like China, while it also bears some analysis about the mixed blessing of a government sponsored art factory being a pipeline for artists making a living.

A free use image of a Robert Rauschenberg

A free use image of Jade Cabbage, the ‘Mona Lisa” of Chinese art

A contemporary painting of Bok Choy by popular Chinese artist Gao Ludi, an example of repurposing the symbol of the cabbage

II : THE DAWN OF THE TECH SECTOR: AN BREIF HISTORY LESSON

For one, a testament to necessity being the mother of invention. For the other, a testament to human curiosity comes when all the other needs on Maslow’s hierarchy are met.

In China, innovations proliferate within a tax funded, highly structured and closely monitored system. In Silicon Valley, innovations are born organically by a natural convergence of ideas, soldered together in garages and shared at uncorroborated conventions and clubs organized by passionate hippie nerds.

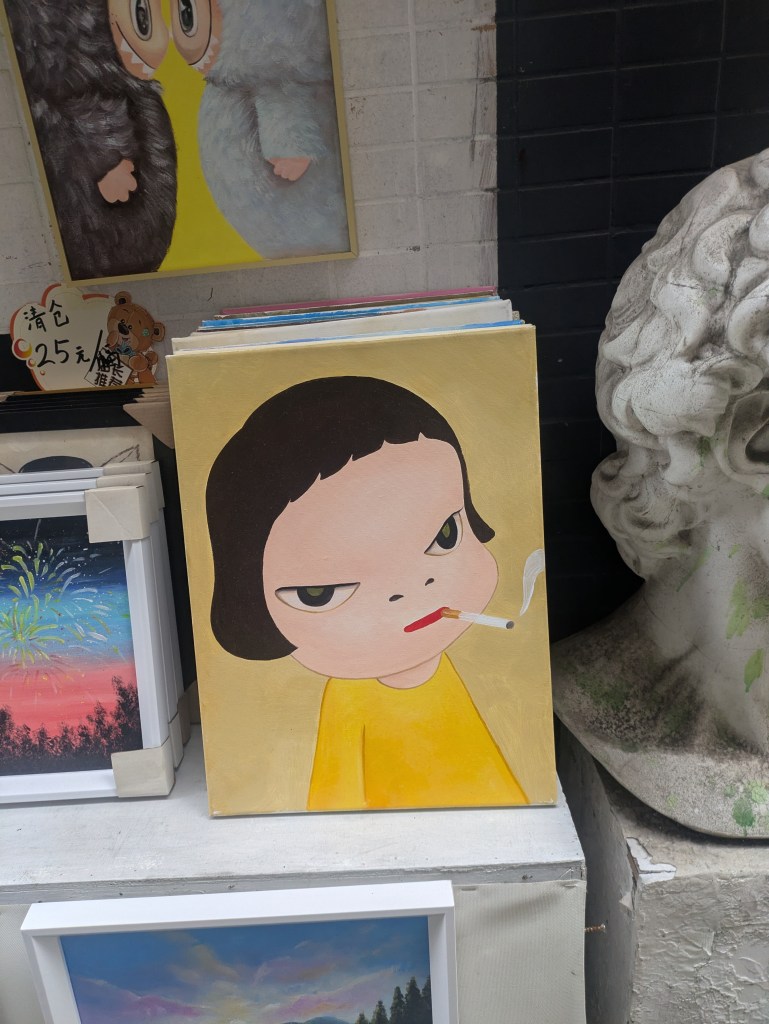

In the behemoth ‘special economic zone’ of Guangdong Province that is Shenzhen, much of the city ascribes dogmatically to economic incentives deemed necessary for China’s survival post 1980. The Dafen Oil Painting village is a historical area, preserved to retain its characteristics pre-1980 industrial revolution. However, Dafen, like the rest of Shenzhen, had to adapt. Existing as a tourist attraction, a marketplace, and a cultural hub all at once, Dafen somehow feels effortless. Artists sit in their studios that double as ‘galleries’ quietly layering paint upon canvas surrounded by stacks of reproductions. Outside, smokers mirror iconic little girls in stacks of Yoshitomo Maras. Inside, artists scrape, layer and dab commissions dutifully, with tourists holding pet turtles and squirmy children enter through the doors of their studios to gaze at the works in progress at their leisure. In the way of much of Asia, it is a carousel of people working, commuting, enjoying, and just living, with glimpses here and there of the juiciest little oddities.

Shenzhen was born of a measure to make China a contender, a project of Deng Xiaoping, the secretary of the communist party who rose to leadership around 1980. At that time, Xiaoping loosened some of the restrictions on trade previously mandated to maintain China’s self-reliance as a communist country. Moving away from isolation to protect the countries ideals, Xiaoping decided to instead push labor efforts towards building relationships around foreign trade, understanding that having stakes in the global trade would provide more stability. Interdependence would strengthen their currency, provide relief in emergencies, and create, eventually, a dependence on Chinese production for other major economies. Foreign relations would necessitate diplomacy, lessening the world’s rancor set upon China at the insistence of America in its unerring goal of demonizing communism. The advent of computers and their effect on the banking system and the stock market, in combination with Richard Nixon’s severance of the dollar from the gold standard in light of the United States increasing deficit (re:Bretton Woods), meant that China needed to adapt. The evidence of this is laid bare in Shenzhen, where China’s need to act fast culminated in the kingdom of mirror and steel we see today.

Enter the identity of San Francisco, with its year-round good weather, Barbary coast adjacent permissiveness around crime, and Victorians with cheap rent, and a cultural revolution is born. A thoroughfare of ideas between the city and the academics at the once tuition-free Stanford University is inextricable from what we now call Silicon Valley. The aforementioned being the mercurial conclusion of a ‘series of tubes’ that connected Stanford University to the hippie movement, serves as the antithesis to Shenzhen. Computer science is inseparable from the divergent thinking that defined post-LSD America, and the confluence of Venture Capital, LSD, and the Jobs/Wozniak type phenomena that came to define that era of bay area culture and the technological innovations that came with it.

Already here lies a fascinating comparison; while Shenzhen’s inception as a tech hub resulted from a litany of political policy decisions that conflicted with, but supported the maintenance of an imperious state, the inception of Silicon Valley resulted from a convergence of divergents, a swarthy cast of lsd-dropping, meditating countercultural renegade dork-geniuses who wanted to change the world and/or make a profit.

Without the creative forces behind tech innovation, all that remains is the benefit of it as an enterprise, which is so often employed as a tool of oppression and extraction.

III: Dafen – a lesson in irony

A picture of artists posing with their reproductions seen in Dafen Oil Painting Village

The earthen chakra of my insights centered on a cultural heritage site emblazoned with a museum at its concourse. Known as Dafen painting village, the modes of production here do not parallel the meandering time tables of creativity, the diasporic nature of artists and their workspaces, or the fussy complexities of pricing relative to reputation that plague the artists I know in America. Rather, the place embodies a practical approach to the problem of sales with an unsexy solution – reproductions. Stacks of Starry Night Van Goghs, reams of unframed Muqi persimmons, and some more rare originals by resident reproductionists lined the exposed brick alleys. The artists who work here also live here, and the government provides subsidies for these artists’ housing. Hearing this, I thought back to the innumerable city hall meeti ngs, petitions with stock prewritten letters, artists zoom think tanks, and tragic evictions I had been privy to pertaining to this issue. Here I was, in a country I had been endlessly warned about for its ‘living conditions’, observing its subsidized artist housing- something I had always regarded as a lofty and idealistic dream. Weaving between round-faced street cats and hot broth carts accepting electronic yuan, I smoked Chunghwa cigarettes and thought about how odd it was that the pictures so highly valued in European art were being reproduced for economic benefit here in this village, while art was subject stringent protocols of censorship in the art world, China edition.

The function of this art was not present, only the enterprise of selling it.

Pictures from Dafen Oil Painting Village

IV: Gorgeous Propaganda

Examples of art encountered in China

The Shenzhen Reform and Opening Up Exhibition Hall in Futian, Shenzhen, China, a massive, foreboding building of glass and mirrors with a rolling, bulging facade defying all the preceding architecture that came before it. Our tour guide was a stylish woman of about 65, wearing asymmetrical patent leather mules and a floral dress with a neckline that payed faint homage to the traditional qipao. It clashed with the pink and purple museum-issue vest designating her as the authority figure on the tour but set a tone for a general verve of presentation presented again and again on the trip; a beautiful presentation, punctuated with some awkward symbol meant to create uniformity and a sense of allegiance, unintentionally undermining the whole idea. Because of a lack of coordinated aesthetic forethought when it came to stamping everything with a seal of designation that all things fell under the purview of The People, something unserious pervaded the effort to do so. She led us through the special exhibition, paying great respect to Deng Xiaoping, the General Secretary of the Communist Party from 1980 to 1987, but who was more largely the chairman/paramount leader of China at large until his death in 1997.

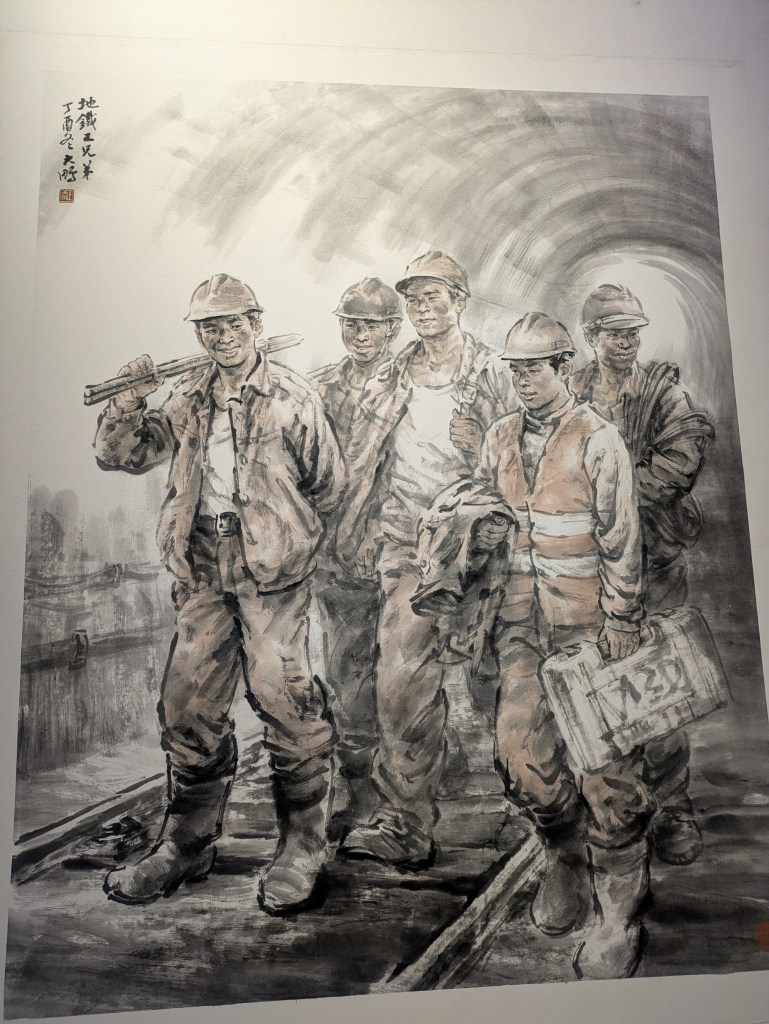

She explained the symbolism behind life sized wax figure dioramas exemplifying the modernization of Shenzhen from traditional Chinese village, to bustling industrial center, with scenes of large outdoor markets selling goods, townspeople riding bikes past public signage that read “Efficiency Is Life”, and interactive miniatures of construction sites for dams where one could re-create a dynamite explosion breaking ground on a dam project. Exiting the exhibition were large paintings and charcoal drawings, the first of which I had seen since entering China. A bloc print featured men scratched out of black ink, wrangling rebar in hard hats. Beyond them a complex, repeating structure grows from the woven rebar, and in the foreground a man shouts into a receiver device, another grapples the wheel of an earth moving vehicle. They are lost to their own individuality in their gargantuan task, their strength a virtue and their focus singular, while the quality of the linework denotes chaos, the half-built structure in the background denotes their ultimate success. In another, a triptych in oil, men and women bend over components of shoes. In the center, bundled up on heavy coats, seamstresses and their male counterparts are illuminated dimly by a doorway with weak sunlight filtering in, the composition dominated with browns, yellows and ochres. A woman glances towards the viewer, hands busy, with an innocent and serene expression. She exudes a contentment with and commitment towards the forward momentum of China and seems resolute in her part in a production line among the others, her equal counterparts in this industrial setting. The other two panels are composed mostly of blues and whites, rows of women at tables alongside a conveyor belt, filled with bine=s of parts cut from different materials comprising different parts of the shoe. The blues of the bins are reflected in their uniforms, denim-colored overalls that contrast beautifully with the morning light coming through from the back of the painting, an opening in the back of the factory floor to the fresh air.

In the third, a charcoal drawing of three men are smiling, laughing and chatting with hands carrying tools through the innards of a mine shaft. Hints of orange and yellow glint from their hard hats and vests, and you feel a part of the jovial spirit of their banter.

Unsurprised by the artwork, I was still bewitched by its power to convey contentment with one’s role within the party. How fascinating it was to witness the unself-conscious way that each institution, person and artist reinforced the value inherent to complying with the group. Foreign to me was the idea that work was to be celebrated and cherished, particularly any work done on a factory floor, or in a mine. A sense of pride was indispensable to creating the willingness of the subjects of these paintings, and this was a slice of the social propaganda meant to get them there.

Purposeful, pragmatic, and executed with the skills prerequisite to impress any person. These was some of the best examples of high art within the restrictions of propagating communist values.

Some art from the Shenzhen Reform and Opening Up Exhibition Hall, unfortunately I didn’t write down the names of the artists or works

V: Reflection – Advice to my Younger Self

I believe that American artists don’t know if they should try to make work independent of the expectations of the rich, independent of the expectations of the viewer, independent of the canon of art history, so we hyper fixate on identity and polemics as the last vestige of what we can reliably attest to. At our worst, leftist Americans can’t yet walk and chew gum at the same time – while we understand the irony that our worldview is a precise and direct consequence of the constitution, our art doesn’t embody a peace with that notion, but instead is distracted by the right wing Americans who can’t understand how direct a consequence leftist identity politics are to a nation founded on freedom to practice religion.

American artists don’t know if it’s important to make work that demonstrates mastery of media, shows an understanding of it, shows anything outside of what can sometimes be frustratingly navel gazing, because the heavy cloud of identity bears upon us in a nation that struggles to find its own when being torn in two by racism and the fundamentality of immigration and indigenous people to its make up. Preoccupied by shouting down the rich and the regime, we are kept in the dark via public education on solutions.

At its worst, postmodern art can be a testament to having nothing to actually say, with no demonstrable skills, and offering that up as if it’s a virtue. It is the most basic instinct of beginner artists with bad educations. Grants from misguided organizations and directives from Marthas Vineyard vacationing curators perpetuate this issue by exploiting artists who use little discretion in exploring these ideas, and we get examples of this fixation that can lack nuance. Otherwise, artists are shuttled into talking about their identity to get attention when they might actually want to make something else, pigeonholed into creating work that would make a rich white collector appear woke by having it, buoying a curator cosplaying being on the cutting edge of undermining hegemony within their institution.

So American artists escape by creating a bubble close to bursting, ballooning on the edges at the pressure of social attitudes about life, freedom and liberty. Those bubbles contain nonsensical behavior, impractical sculpture, emptyheaded vanities. It’s sometimes completely delightful, but it can at other times feel lacking in substance.

In China, identity is the hegemony, in America, it is the polarity, and therefore the dominant force driving our conversations. This obsession of the American spirit prevails not despite, but because of oppression – your identity is the crux of all that must be driven forward, the locus of intention. Without prescribed practice of that identity, it’s meaningless. These identities become fraught with self-doubt, and we bark louder, but continue avoiding a bite. It is a tokenized critique of generations without enough gumption to articulate a real path forward, swimming in debt and worthless education (one that offers insight on hegemony, without the inclusion of critical organizing skills).

While the conundrum pisses me off, I would also rather that it didn’t define my practice, as an artist, but I should also recognize that identity art is at its least interesting when exercised by a person like me. That said, we should all be mixing out lifestyles as artists with actionable items to make improvements in the world.

A bloc print from the Shenzhen Reform and Opening Up Exhibition Hall

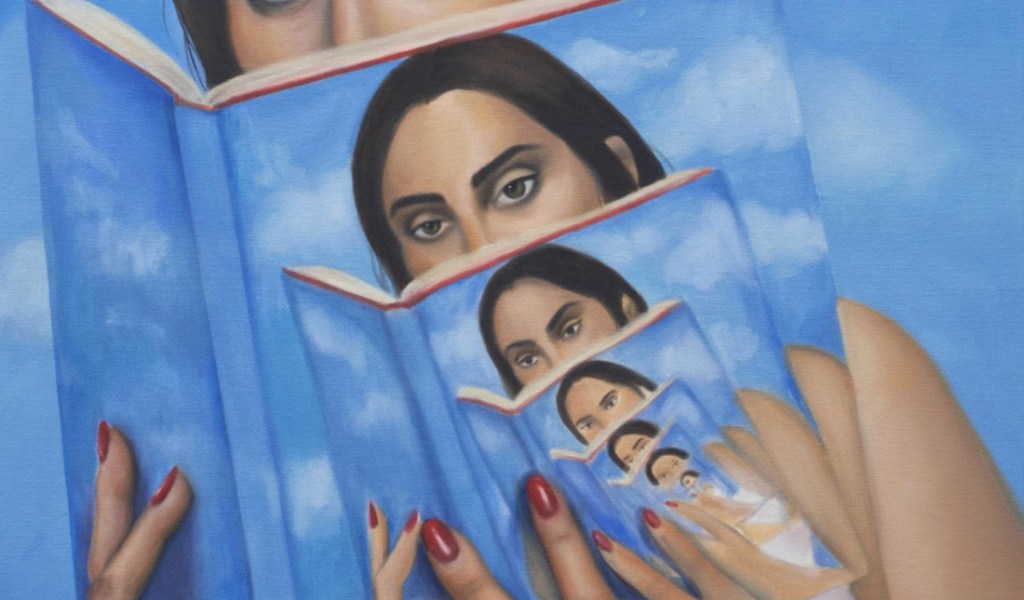

A painter who frustrates me, by playing coy with this subject by exploiting it, Chloe Wise

VI: Conclusion

This is a case study of a method of art production I witnessed in a single institution and its implications for the overall system, not a comprehensive analysis of the current state of contemporary art in China. In a country with a complex interplay of censorship norms and cultural insularity, historical struggle against imperialism that informed its political evolution, and an educational system that emphasizes propaganda within its art institutions, I would not profess to have spent enough time in China to make those kinds of statements. I notice, however, a common thread between three Chinese artists who are well known in America. They share an inability to abide by the aforementioned taboos within China: Martin Wong(an alumni of my college), Ai Weiwei,(a name that, surprisingly, drew no recognition among any Chinese person when I asked) and Hung Liu (the teacher of my teacher, who I have previously written about) share renown as a result of the narratives in their paintings. Allegories of erased history, socially muzzled identity, and how class dictates lifestyle resonates with Americans. Distressingly, I wonder: do non-white first generation American artists have a better chance at success when they fit into a prewritten narrative about China? Under all of that pressure, how could any artist put brush to canvas? Yet, they do. Artists persist, and a binary of good or bad won’t help me understand the differences of arts utility.

Art at its most frustratingly obtuse or at its most meaningful and powerful, does not exist in a vacuum. It comes fourth from an act of pulling out from the ethers an exactingly phrased, compellingly depicted truth about the larger picture. Apparently, we can sometimes recognise this inherently on a subconscious level, as exemplified by a recent discovery that Jackson Pollock paintings contain the selfsame fractals that hypnotise us into staring at waves in the ocean. How that happens doesn’t always have to adhere to such a strict formula, and the result will embody the vernacular that the artist inherits from their culture.

Its utility is present within the narratives of people who understand it. Unfortunately for capitalists, this means screaming into the void as entertainment for the rich, frustratingly reinforcing the status quo. This necessitates disharmony. This raises questions about the value of individualism in how it culminates in creative value, but inevitably it becomes a commodity, a shareholder value. For a shining moment, though, we had someone remember what it meant to be human, who managed to weight that moment into a visible anchor for us all.

Fleeting as these moments are, meeting them is good goal for the artist.

Leave a comment