This week, I visited the temporary exhibit currently on display at the SFMoMA, six rooms of paintings by artist Amy Sherald, entitled American Sublime. Sherald first gained national recognition for her iconic portrait of former First Lady Michelle Obama, which was unveiled at the National Portrait Gallery and the White House as Obama completed her second term as First Lady. Sherald painted the portrait alongside Kehinde Wileys portrait of Barak Obama, both of whom are black portrait painters who prefer to find their subjects on the street, and are interested in recontextualising the black image in art history. Both artists also had solo exhibitions in San Francisco within a year of each other, with Wiley’s show running at the De Young Museum until late 2023.

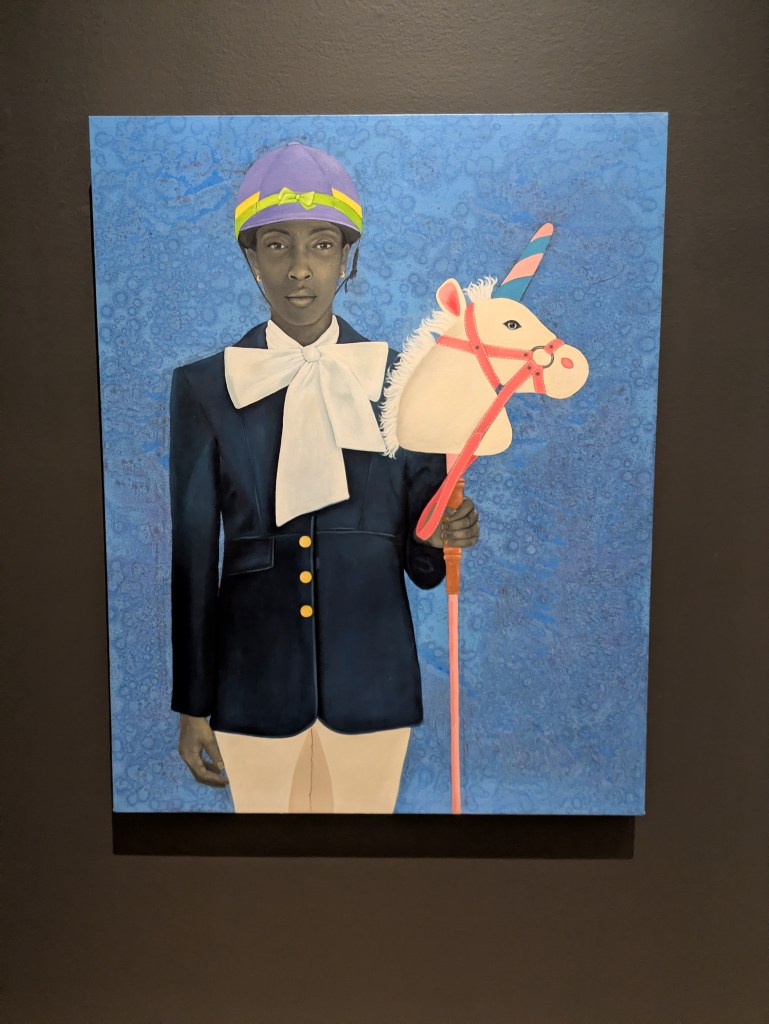

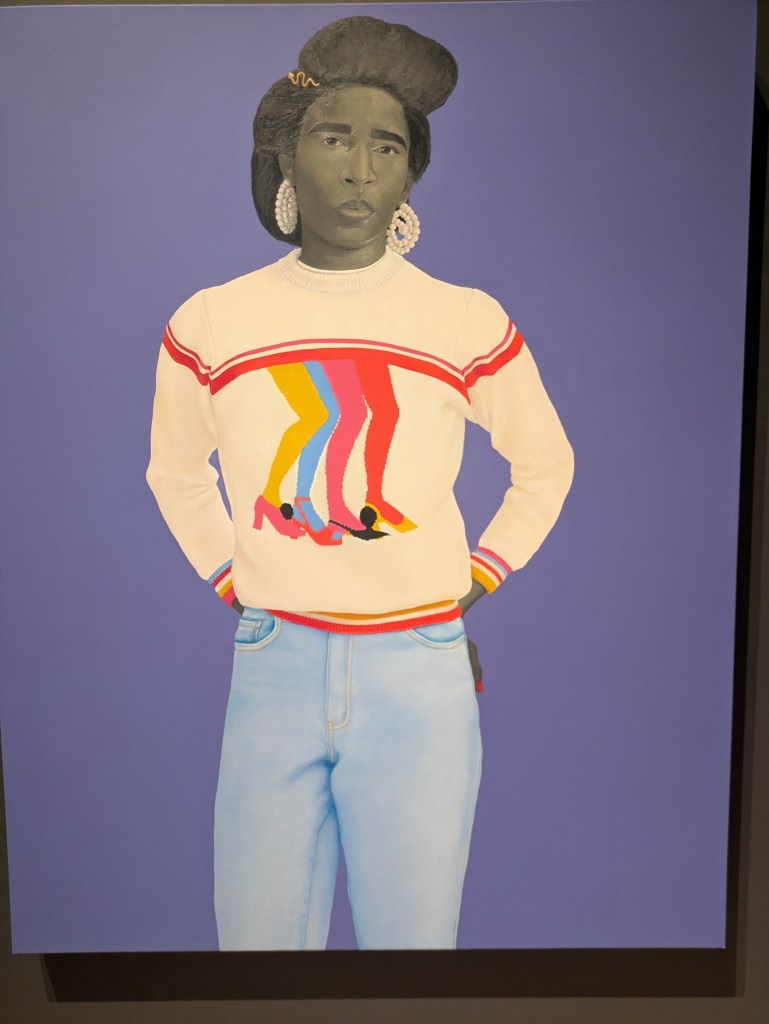

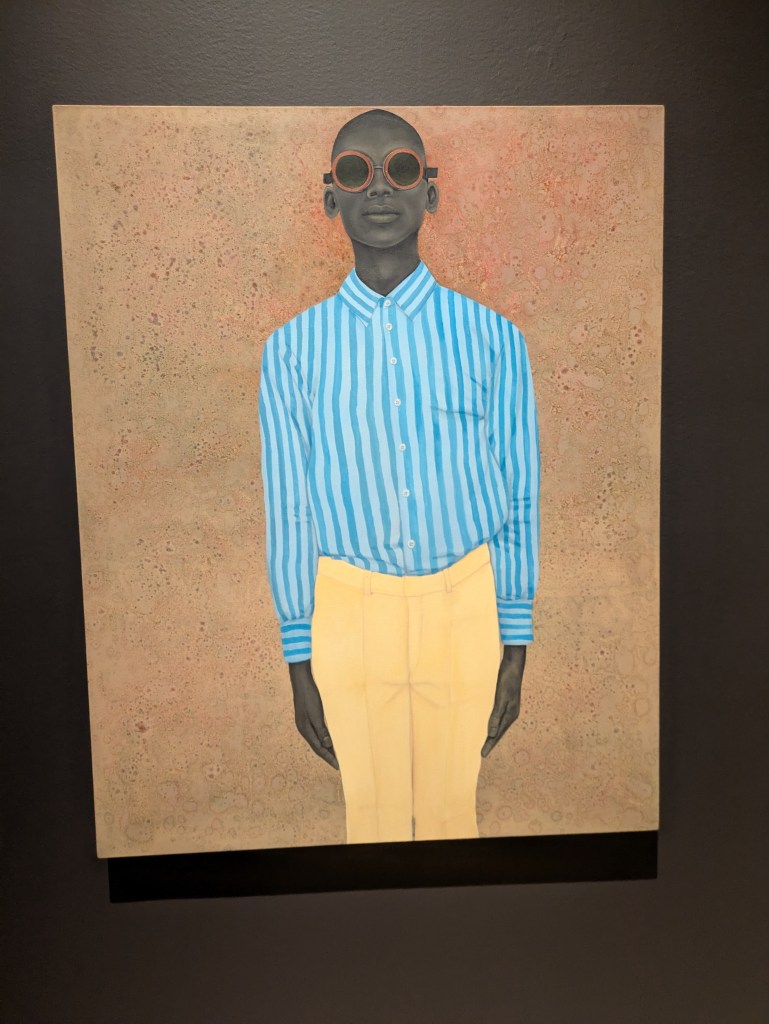

The paintings in this exhibit span from 2005 to the present, with 2005 marking the year Sherald found her distinctive style and technique, around the age of 35. Sherald is known for excelling at executing the subtleties of expression and idiosyncrasies of the face that, at their best, draw breath from the room. Some of her earlier works introduce a whimsical, imaginative quality in the chosen clothes and props that accompany the sitters, infusing her portraits with levity and intellectual curiosity. These compositional choices lie in marked contrast to the uniformly blank, stoic expressions of her sitters. While the backgrounds, clothing, accessories, and even toenails of her subjects burst fourth in vibrant, phosphorescent colors from their tight frames, the faces are uniformly gray and sober. From the beginning of the exhibit to the end, her intent and the results seem to blur together and separate, to focus and unfocus like a concussion, two fingers, no, one, no… By the end, Sherald whips her work into a sometimes surreal, sometimes so-real-you-can-smell-it ouvre of curious, sincere inquiries into the task of depicting blackness. Overall the exhibit is composed of work that explains a story of her becoming, rather than a lifetime of achievement. This isn’t meant to be a perjorative, rather, an interpretation of the works as a story of the artists slow, deliberate liberation through and within painting.

Sherald explains her choice to paint her sitters as grey and stony-faced, saying that she wants to elevate the human presence of her subjects, placing their skin color in a secondary role to their humanity. By giving her sitters neutral, relaxed expressions, Sherald avoids depictions of the black body in a state of performance, she wants to show them being, rather than doing. The colorless skin and affectless expression places the portraits in a historical context of portraiture requisite to color film and footed in long exposure times wherein the sitter couldn’t hold an expression or pose that was unnatural for long enough to get a stable shot. As a result, her portraits appear dated and opaque. The results are mixed. Exploring the first two galleries, I was unnerved that I didn’t quite experience the sublime response that others had described at seeing Sheralds work. At other moments, the paintings evoked the whimsical absurdity of the art/film zeitgeist of the early-mid-aughts, Tim Burton or Burton-ish films like Alice in Wonderland, A Series of Unfortunate Events, and Big Fish, or paintings like those of Marion Peck and Mark Ryden. Distinctly campy.

Sherald says as much in interviews, that she draws a lot of her inspiration from films about imagination, and in particular, she does favor Big Fish (I do, too.) While I appreciate getting to know who Sherald is in the context of these explorations of narrative within the framework or her black portraiture series, the fusion of serious themes with playful, carnival-like novelties in these portraits occasionally muddied their context, making it hard to fully interpret the intent. I’m not entirely sure there was any, which was strange to encounter in a gallery at a major museum. It was sort of disarming, in comparison to Wileys deeply serious, art-factory-manufactured, and meticulously executed exhibit at the De Young from the previous, previous autumn. Whether intentional or not, this affect drew me in and gave me a sense of warmth toward Sherald. The humanity of her process as an artist trying to find coherent vocabulary emerged more clearly as the show bled into her more recent and very large scale work, work she has been able to make because of a larger studio, more assistants, and more time due to the recognition she received after painting Obamas portrait.

My stomach dropped as I turned into the third room, featuring the Vanity Fair commissioned September 2020 portrait of Breonna Taylor. Taylor is depicted with a silken blue dress draping her form, and a cross pendant around her neck framing a subtle heart shape at the chest between the dress’ neckline and the gold chain. The expression she wears, a familiar selfie we all came to associate with Breonna Taylor from its use in news reports and social media posts about her story, intensified the strength of the visual experience with deep emotional reverence. Any reservations I had about Sherald promptly dissolved, as she held an entire room of people in vigil with her ever-carefully lain strokes of paint. The enormity and gravity of Taylors life were so presciently contextualized by the way Sherald held every ounce of pain in her brush and moved it across this project so lovingly, carefully, and consciously.

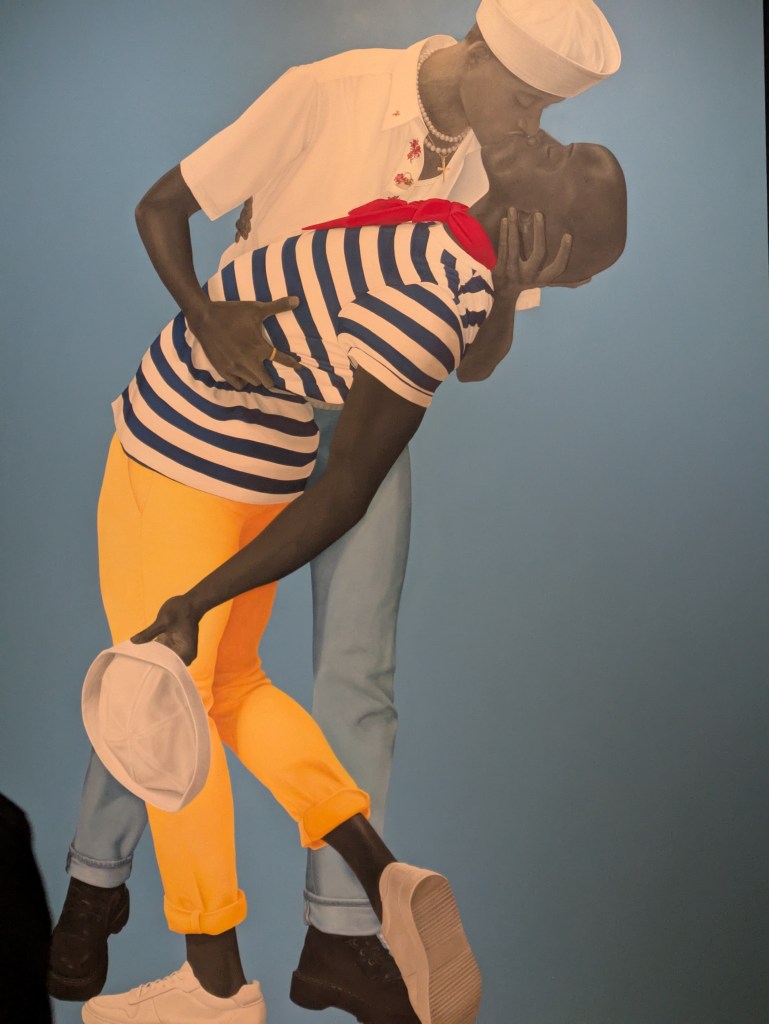

Spanning the five rooms were four large paintings that could have been a full exhibit of their own. The were painted in HD, with backgrounds and narratives that completed the portraits as complete paintings with a message, a composition, and an insistance upon being an ebb in the flow of art history. One of these pieces, a spin on V-J Day in Times Square, depicts two black men holding each other in a deep, intense kiss, their outfits reversed from those worn by the original pair of people in the famous Time Magazine photo (of a sailor planting a deep kiss on a nurse held sway-backed in his arms). The man standing upright wears a crisp white shirt embroidered with roses, with the man held in his arms, under the spell of the kiss, wears a white and navy blue striped shirt with a pair of tight yellow pants, a nautical streetwear outfit. This painting takes two uncommon depictions to task, that of two gay men engaged in a moment of tenderness, and one of two black male Americans replacing two white Americans celebrating an iconic moment as victors in a war story.

The next was a take on “Lunch on a SkyScraper”, in which Sherald depicts a single black man on a praying-mantis-green high beam that cuts diagonally across the frame like a single stroke abstractionist legacy painters most self-assured gesture, a radical diversion from her usual centrally located portraits.

Third was not necessarily art historical, but obviously harkened to black land ownership. It was a painting of a black man staggered atop his brand new John Deere tractor, the tires so freshly minted I could smell the rubber, and each blade of grass beneath him treated with the care of a royal eyelash in a dynastic portrait, placed just so.

Fourth was also not art historical, but felt placed in a tradition I cant put my finger on, an unsettling portrait of a black boxer wearing Sheralds iconic expressionless face. Because he was an athlete in a position of victory, it fit well here, and the viewer stands beneath him, his eyes cast slightly downward to meet yours. Looking down his body, the boxers shorts end in eery space, with no legs, and his gloved hands, rendered so precisely, hung at the sides of the stool his torso sat upon, the silky folds of his boxing shorts draped haphazardly against the edge. Unsettling is the word I would choose to describe it, and I get this sense that as Sherald paints on, she will lean in this direction more and more.

I get the sense of Eureka! That this is the ultimate conclusion that she wants to lurch her self into, as asserting nothing so pointedly decipherable about blackness as a simple reversal of roles. Not to be obfuscatory, but to be as undecipherable as life itself, for everyone, and not to be caged in a continuum of black suffering and enslavement that defines the narrative for so much art about black experience has had to be, until, perhaps, this moment. She has proven that she can do that, and now, she can do whatever she likes.

Sherald’s journey as an artist is still unfolding, and this exhibit provides a fascinating window into her evolution. While her earlier works offer glimpses of her potential, it is through this progression that we witness her developing mastery over her craft and the layers of meaning in her exploration of American, Black, and art history. I don’t mean to suggest that her early work is weak or poorly curated, but rather that this show allows us to witness the unfolding of an artist’s vision—one that speaks to the complexities of identity, presence, and history. It is an exhibition that invites us to reflect on the artist’s process as much as it asks us to engage with the powerful subjects of her portraits. The exhibition was a testament to her growth, and I found myself falling in love with the artist’s dedication and the time she has spent refining her voice.

I am interested in her forays into making things that haunt, disturb, and confuse us as viewers, but whatever Sherald does, I am glad she has what she needs to do what she has to do, and getting to see what a black woman does with her freedom is a thing of joy forever.

Leave a comment