In recent months I have poured over a couple of biographies of famous female artists, two of whom happened to migrate from New York City to the area of the southwest which we now call Santa Fe, New Mexico, also known as the ancestral land belonging to the Pueblo and Navajo Nations.

I made it a priority to visit their museums, installations and exhibits (though I was not able to visit Ghost Ranch in Abiquiu, and Agnes Martins house in Taos is, as far as I know, not open to the public. ) That consisted of the Georgia O’Keefe Museum, in Santa Fe, and the Agnes Martin “Chapel” at the Harwood Museum. Fate also lead me to a new artist with a sizable exhibit at the Harwood Museum, Raven Chacon, more on that later.

New Mexico is a vast country of open space and roadside attractions of the anachronistic variety. Teepees erected for tourists remain from an earlier time, alongside markets selling blankets, baskets and pottery, yellow billboards with heavy black font advertise fetishes and authentic jewelry, and national parks erected for sites of ancient petrified wood and petroglyphs pepper the landscape. The presence of indigenous people is abundant, in commerce as well as public art. Every town had large murals, many had decorated overpasses with common triangle and diamond patterns also found in weaving and pottery from Navajo craft. Many of the small galleries Santa Fe is known for seem to specialize in contemporary work from an indigenous lens.

Being from California, I found the coexistence of (what seemed to me) exploitative roadside attractions mingled with clear indications of municipal prioritization of indigenous voices a little jarring. Upon closer inspection, though, this isn’t unlike California, the highways are lined with bells that recall the original road that connected the 13 missions, buildings the Spanish erected to strip indigenous people of their culture. In McKinkeyville, a giant totem pole built by white people stands as a tourist attraction behind a grocery story, surrounded by asphalt. At the same time, a sacred Shell mound in Berkeley was recently returned to the Ohlone tribe, and an overpass mural was commissioned by the city of Eureka to be painted by an indigenous artist, while museums of stolen artifacts pull tourists to this day a few dozen miles up the road. Somehow the small aesthetic differences drove the oddness of this pastiche of acknowledgement and exploitation home.

I visited the Harwood museum in Taos, about an hour and a half north east of Santa Fe, to see the Agnes Martin room I had read about in her biography. Martin designed the room herself, and the 7 paintings inside are part of a series, making it the only collection of her work available for public viewing meant to be exhibited as a whole. The SF MOMA has a similar Agnes Martin room, with an hexagonal shape and a large round cushioned bench in the middle of the room, the view the sic paintings from any angle you wish. Both are meditative, quiet, and welcoming, but one doesn’t have the same natural lighting flooding in through a ceiling light, nor a set of benches designed for the space by Donald Judd in collaboration with Martin (they were good friends). The work Agnes Martin made was in relationship with the light, atmosphere and colors of the desert southwest. There is something to be said of things seen, appreciated and held in the place they were born that we so rarely experience at this time in human history. An appreciation for things in their native place has to be cultivated by those of us whose identities aren’t tied to any one place, and whose commodities, too, are built and shipped at the behest of wanton trade fluctuations and centuries of immigration, colonization and westward expansion undocumented except for in our epigenetic scrolls.

Back to the art: Agnes Martins work is the kind of art that presumably garners a lot of dismissal from art museum patrons(presumptions being, by their very nature, presumptuous, I venture to assert this anyway). While the collection at MOMA does have its own quiet, meditative wing, I usually find myself alone in that room, with patrons occasionally cycling in, sitting for the requisite 16 seconds, and cycling out. This isn’t a criticism of them, its just a common occurrence in modern art: overly simple work is scrutinized and dismissed by the general public, and in my view, is elevated by art critics because of the ire it draws. Because of the discipline it takes to look closer, the acquisition of these works might serve the more probing minds, and they are an important representative slice of what was going on with abstraction in the fifties, sixties, and seventies. The tricky thing about this is that sometimes, these sorts of acquisitions are the totemic wise choices that make an art institution respectable; they saw something valuable in what the public would dismiss unless a museum lauded it. At other times, someone mistakes an artist who takes on the self punishing task of making something boring on the basis of an intellectual insight about Painting as smart, important work, and the public has to stare at it and wonder what it is they don’t get for 40 years until it gets stored in a refrigerated locker in the museums basement.

I think that’s one of the things that draws me to work that I dislike or am bored by at first glance, which is how I make a trip to a museum last twelve times as long as the average person might spend. There is something to be said for work that quiets the soul, calms the eyes and recalls in the reptilian brain all things Golden ration. Jackson Pollock’s work was recently scanned and analyzed by AI and it was discovered that the work contains infinitely smaller fractals, like the kind we see when staring at waves crashing on the beach. Maybe if looked at ‘correctly’, Martins work could have a similar effect. I can’t seem to trust my own experience, though I do frequently visit her paintings. I guess I like them.They don’t tell me what to think one way or another, they just are. It’s like looking at someone and not being able to project onto them, so you just be.

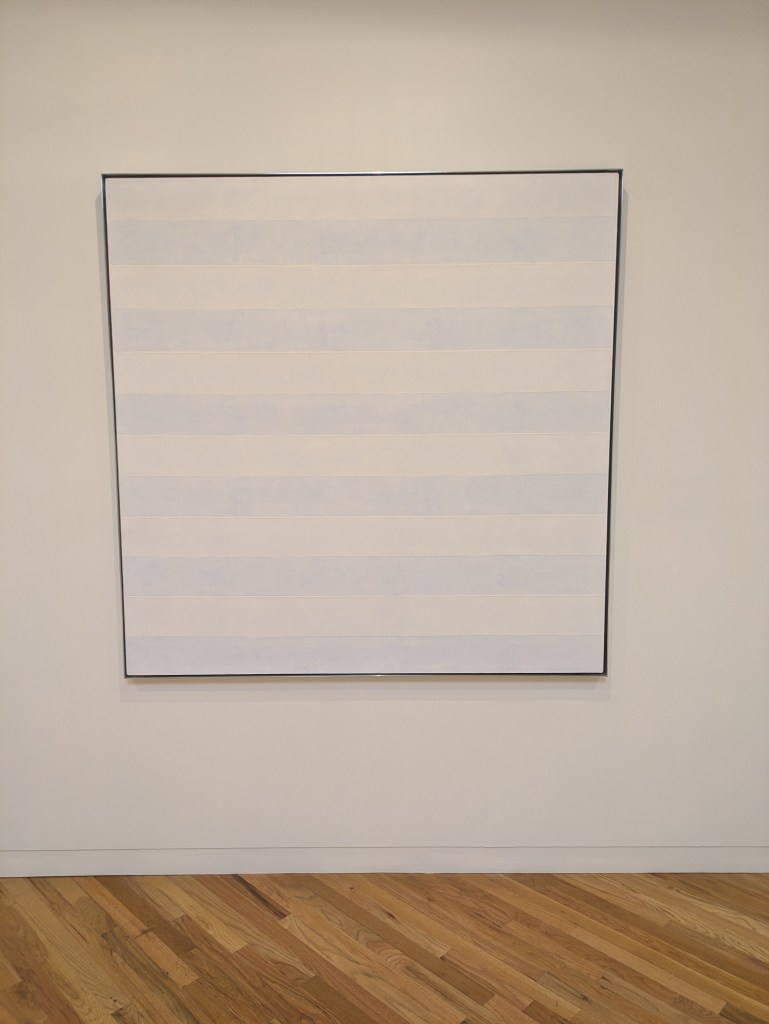

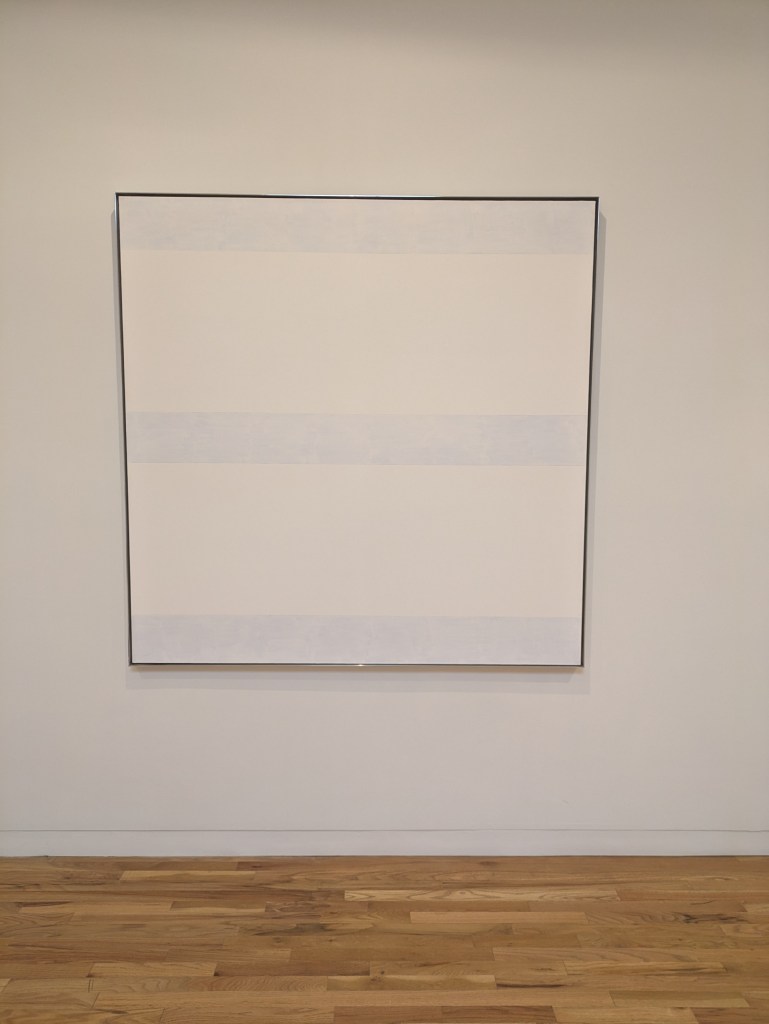

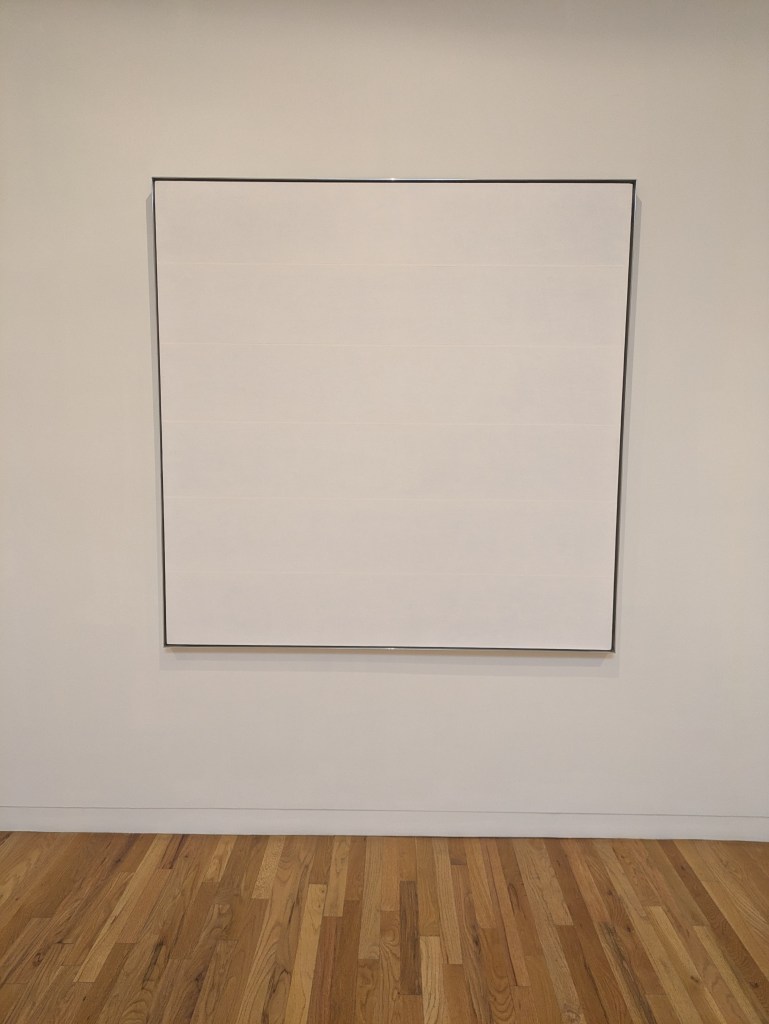

Agnes’ works have been called meditations on the sky, wide spaces, and her insights on zen and mastery of inner peace; they are almost intangibly delicate, quiet, and seem to grow, shrink, and breathe as you stare at them. They have a power to them that seems to appear as you sit in their presence, and while she did not specialize in optical illusions, the lines, grades, and faint color shifts transfuse breath into the work.

Because of how the work is arranged and the benches are positioned in the middle of the room, you have to rearrange as you look at each painting, and the paintings are arranged like a cross with an empty hole in the middle. I enjoyed the flexibly I had to put my feet in the middle of a pit. The benches were efficient little orange boxes, each one made unique by how the piece of wood in the middle of the box was angled. Agnes Martin professed to loving the color orange, the color of happiness according to Zen Buddhism.

I felt an acute sadness sitting with this work. Stripes of grey blue and white painted painstakingly across the canvas in horizontal lines, the canvases varied in the thickeness of line. This was the only thing that distinguished one from another, echoing the Donal Judd benches. I felt cold looking at them, and while they didn’t feel resigned, they felt like someone looking directly into a void and finding, still, an essence in it. I was surprised when I walked out of the ‘chapel’ to read the titles (something I usually try to save for after looking at a piece) and read that the titles were “Love”, “Happiness”, and “Playing”. Agnes was an admirer of Matisse and Beethoven, and attributed their power to their skill at depicting joy. These paintings were expressions of joy, to her, but nothing about them made me joyful.

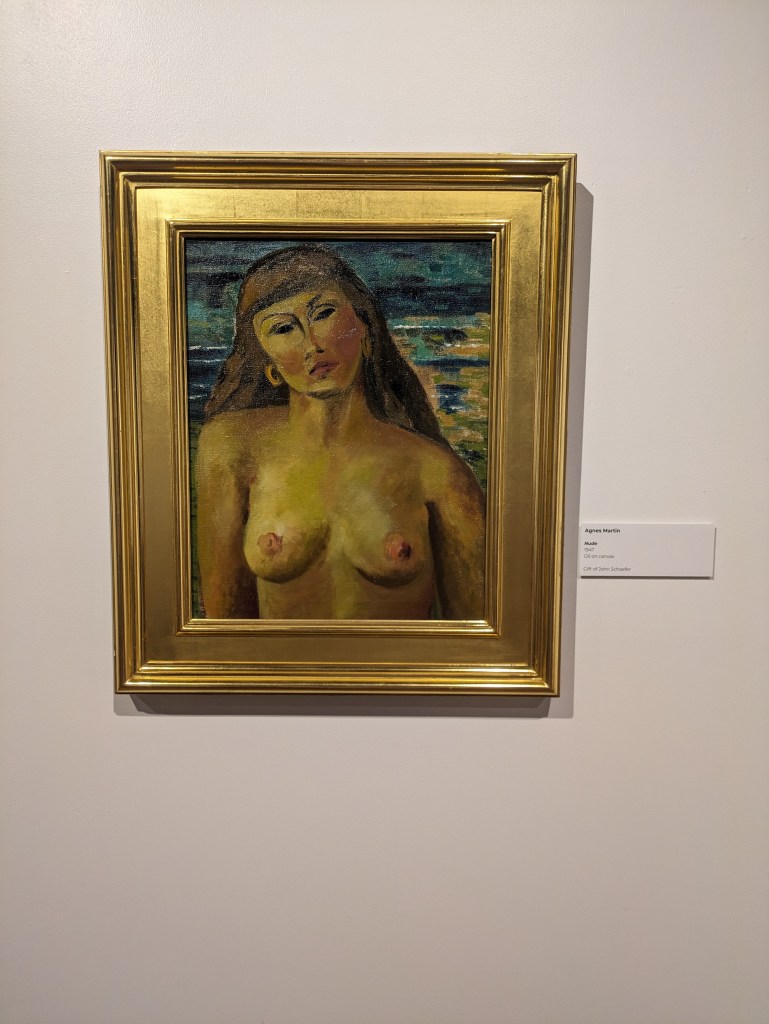

In another room was an early figurative painting, which was actually a very impressive acquisition. Martin, like O’Keefe, was exacting, and constantly destroyed her own work if it wasn’t to her standards. She transitioned from figurative painting to abstraction and never returned to representational work, and I wonder how this painting survived. Knowing Martin moved to Taos alone with very little money and no art patronage, and that she starved almost to death multiple times in the beginning of her time there, I would venture to guess that this wouldn’t have survived a winter where she needed firewood to burn for warmth, as it was on panel.

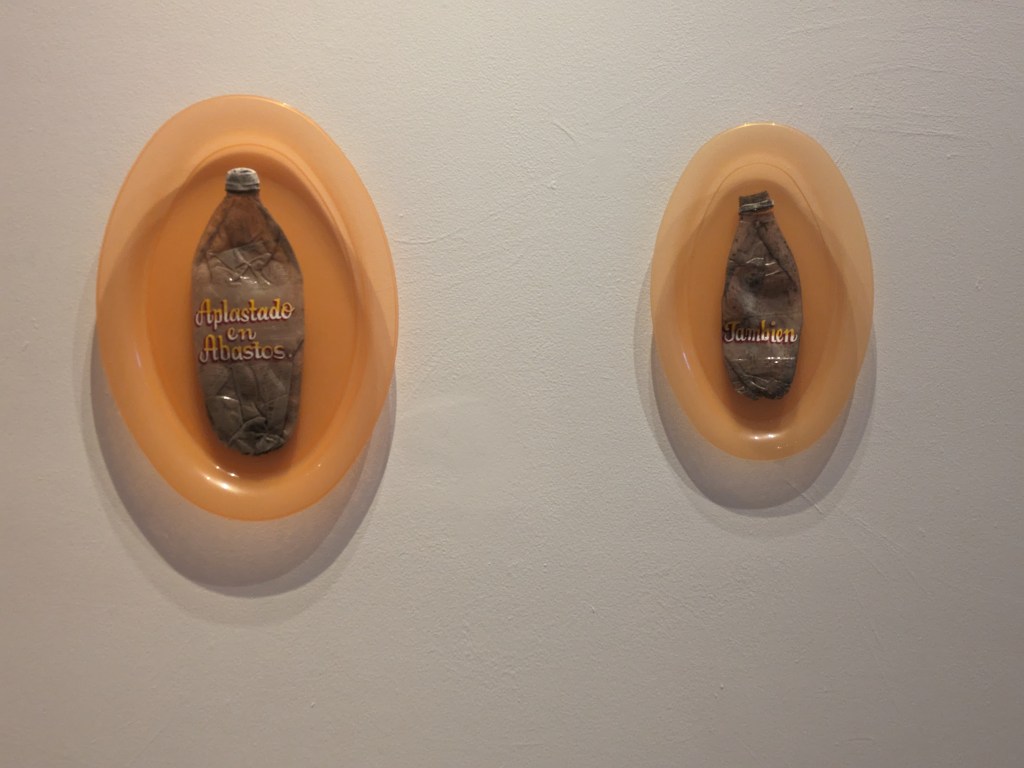

Overall, I liked the way the Harwood Museum was curated. It proved to be a very satisfying experience for such a small museum. Apparently there was an exodus of Los Angeles Pop Artists into Taos in the 70’s and 80’s and an entire room was dedicated to works acquired from Donald Judd, Larry Bell, Ronald Davis, Ron Cooper and Ken Price, which was a pleasant tonal shift from the quiet existential beauty of Agnes Martins ward.

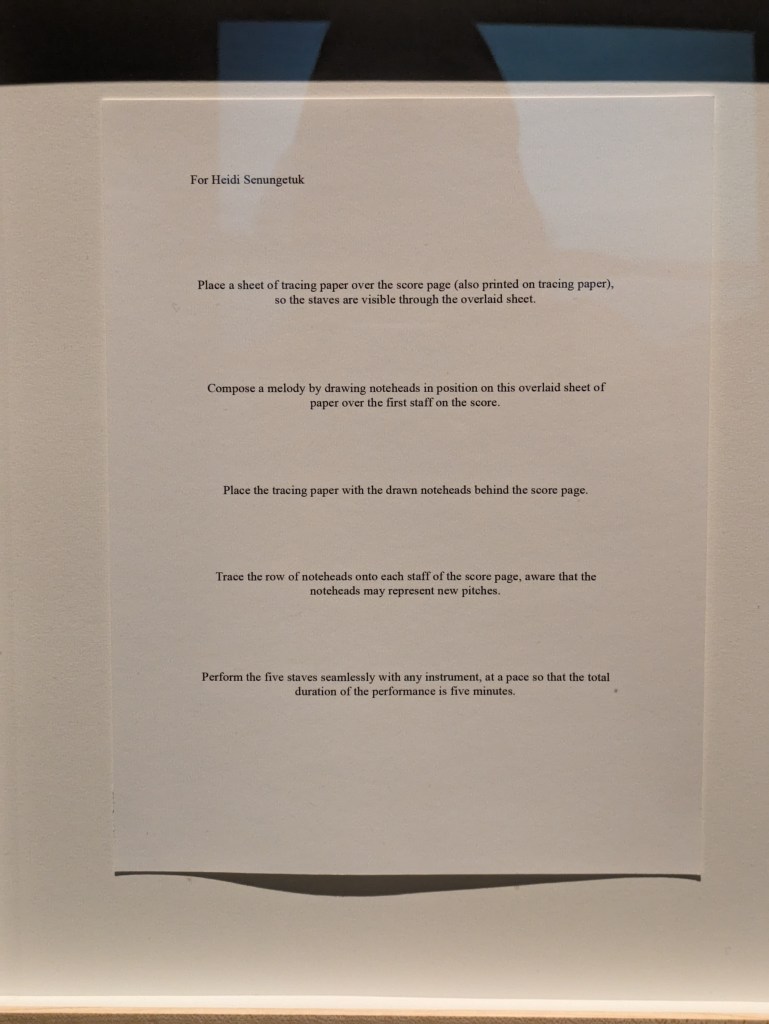

Also on view were these really innovative, weird relational music pieces from and artist named Raven Chacon.

The pieces were part instructional art (think Yoko Ono), part poetry(think Joy Harjo), and part experimental music composition. Chacon used native weaving patterns and other insignia to dictate the composition of the stanzas and sometimes the rhythm of the musical compositions.

On the other side of the room displaying Chacón’s framed performance instructions were a series of three projections. These projections were videos of native women, standing in sites of historic massacres that are historically unacknowledged, covered up, or denied. These lands were stolen in violation of treaties, and still haven’t been returned. Captions on the bottom of the videos provided translations for the lyrics, and the songs ranged from prayers recited to a creator, to detailed descriptions of massacres on sleeping women and babies by white colonizers. The singing was accompanied by drums, and the women performed alone, creating an irreverant image of resilience and resistance.

The range of the curation at this museum, and in this particular exhibit, was essential to gaining a better grasp on what contemporary art movements are taking place in rural New Mexico (the answer is: highly experimental and exciting ones). It was so radical to see an artist is doing something avant garde in a community as small as Taos,, and when I talked to the security guard about the communities reception of the work, which has included a few performances by Raven Chacon, he told me, “Think say it’s pretty weird.”

I have great respect for small rural museums giving space to something that doesn’t fit cleanly into a box of this or that type of art (i.e. painting, performance, music). Indigenous voices in particular are exciting to hear in a museum space breaking from what is easy to understand or digest to create something relational. I have studied work by Rirkrit Tiravanija, Yoko Ono, and James Luna, so it’s not like people of color don’t have a huge part in defining the canon of performance art and conceptual art. Even in the art world, this work is weird and niche and controversial. It’s meant to be. It just seems more sincere when it comes from people who are forced into such a small box of who they are allowed to be in a world dominated by white artists. Freida Kahlo said of the surrealists and their performances that they had no actual personalities, and they were all in a room together trying to out-weird each other to seem more interesting. Do I fully believe this? No, but I think there’s something to it…I guess I am not saying it enjoy it any more, or less depending on the ethnicity of an artist, I just enjoyed getting to see someone current who makes weird work from an indigenous lens.

I wrote my own charter for a performance art class that I petitioned the Dean to give me credit for in college, and spent 6 months performing my own curriculum that I picked out of a book called “DO IT: A compendium of instructional art” by Hans Ulrich Oberist, so instructional performance art has a special place in my heart, and I don’t see much of it in museum spaces. I think the mixture of pattern and symbolism that was personal to the artists heritage, in combination with the instructional and musical components, grounds these pieces in a way that instructional performance art can lack. I enjoy to silly experimentation of Andy Warhol Happenings and Laurie Anderson as much as I do the psychologically intense work of people like Marina Abramovic, but these had a musically technical bent that I found sexy.

Georgia O’Keefe has a dedicated museum in the heart of downtown Santa Fe.

The building is red clay adobe, with cool cement floors and natural light flooding in through the ceiling in some of the rooms, subtle ochre-white lights illuminating the work gently in others. From the minute it opens, it is flooded with visitors.

The Georgia O’Keefe museum is far from being the only art institution in Santa Fe. The city also has over thirty museums and cultural centers, ranging from contemporary, to contemporary indigenous, to historic, site specific work, and experience based installation. The art available to citizens and visitors of New Mexico could easily span over a year to take in, and the diversity of approach the institutions take to collecting and exhibiting work leaves no one wanting for anything. The Georgia O’Keefe museum was unique, though, in its dedication to the artist alone. I can’t argue that it isn’t justified; some say she is the most talented female painter to of lived, and I am turning over and over in my mind how true I think that is. She seems to have been one of the most dedicated.

Having finished Portrait of an Artist; A Biography of Georgia O’Keefe by Laurie Lisle shortly before this trip, I had something to compare to the way the museum represented her. Keeping in mind that this museum is probably funded by an endowment and run by a board of her most ardent fans and loyal supporters and collectors, I had some insights about the Museum, about Georgia, and about what an artist can mean to a city. Judging from the line, it is also a lucrative tourist attraction, and most towns don’t make bones about things that bring in much needed tax revenue, and Georgia O’Keefe wouldn’t bring indignity to any place. I just think about the accounts from residents, neighbors, and employees of Georgia that she wanted nothing to do with anyone in the community (except for the children and Abiquiu, whom she invited to dinner and built a school for). I guess this isn’t a qualifier for someone being a local legend, and I don’t know that it should be anyway.

Georgia went to teachers college and art school on the west coast and had some friends who showed her work to Alfred Steiglitz while she was teaching in Texas. They ended up getting married and she left Texas and teaching behind to pursue art in New York.

After a decade of shuttling from New York for business, to nearby Lake George for respite and solitude, O’Keefe was offered a space to work in another artists studio in Santa Fe. She took it, having visited a decade before and falling in love with the place, but getting caught up in her marriage to Alfred Steiglits and he constant exhibits at his gallery, An American Place.

After being offered this studio space by someone who was called the Gertrude Stein of Santa Fe, Georgia slowly transitioned to having half her life in New Mexico, and half in New York. Because of his advanced age and need for proximity to medical treatment, Steiglitz could not join Georgia.

She was a staunch person who gave no nonsense advice, on the rare occasions she bothered to talk to fans, though she never took students and didn’t particularly care for the swaths of admirers that appeared at her gate or approached her in the street. She would say things like, “You’re not successful because you aren’t working hard enough”, though she was supported by a rich husband …and didn’t even live with him…

Alfred had very staunch ideas about who artists were and what their art should be, and decried the depression era works progress administration and his presumptions about its impact on Art and the undeserving artist recipients, muddying the water for real artists such as himself. He also didn’t care for the Mexican muralist movement that came of the push for communism and raised up the working class,. He was protective of Georgia and her participation in these movements. In a rare role reversal, he dedicated much time and effort into bolstering the prices of Georgia’s value through his museum and his dealings with collectors.

Georgia could be a rebel, though. She went against his wishes and took commissions, once for a powder room at the Radio City Music Hall, and later for a pineapple company. On both occasions, she didn’t complete her commissions to the satisfaction of the institutions. She did, eventually, paint a pineapple for the pineapple company, but only after she returned home from her all expenses paid trip to Hawaii in order to paint a pineapple, which she didn’t do because she thought pineapples were gauche. She sent them instead some paintings of Agave plants, which the pineapple company refused. The pineapple company insisted flew her a single pineapple tree in a small plane in order to receive her commission on time for the packaging they were going to use the painting for. As for the powder room at the radio city music hall, she came down with mental agitation and quit the mural half way through.

Also, she showed up to a workers hostel in Hawaii hoping to board there and was turned away because she didn’t do manual labor. She was very bitter about this and made multiple attempts to be let in, arguing with staff and managers that she was, in fact, a worker. She was never admitted and ended up renting a house of her own elsewhere on the island.

Georgia ultimately just wanted to be left alone to paint, and she wanted to paint what she wanted to paint and nothing else. She didn’t need friends, didn’t really talk with the community of Abiquiu where she lived in New Mexico, and slowly stopped speaking with her friends in New York as she aged and just kinda, didn’t like them anymore. The woman was extremely driven, dedicated, and committed to one thing, and one thing only, and that was painting. I don’t know that I have read biographies of any other artists where their focus was so singular, and her work is really, incredibly beautiful.

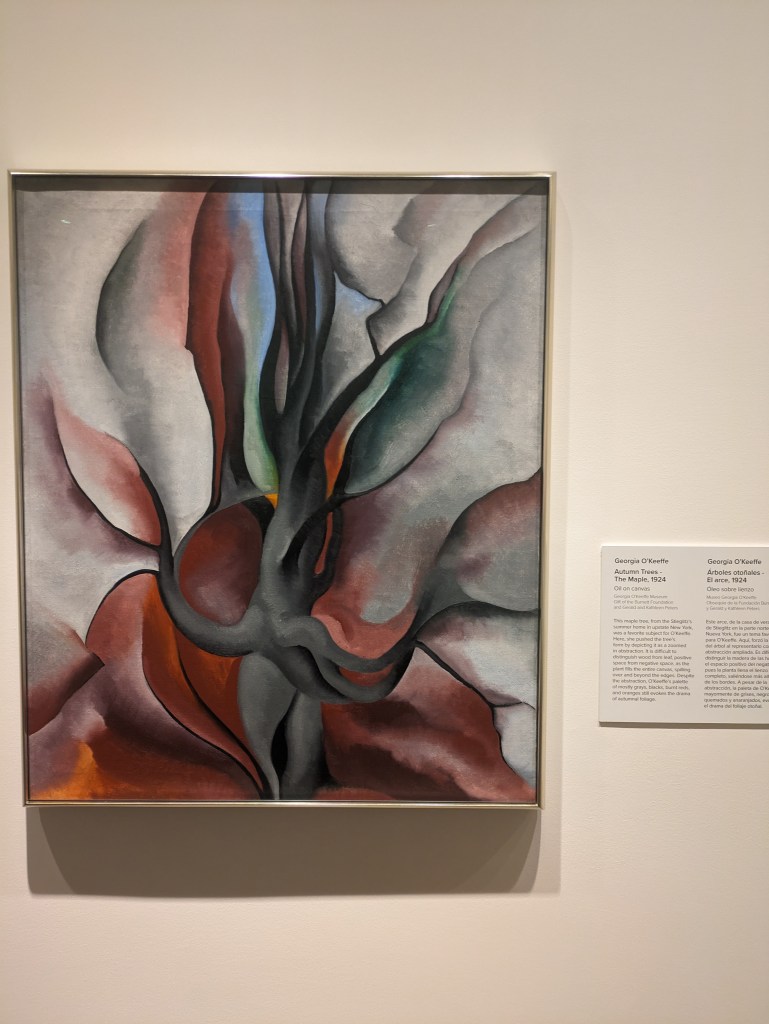

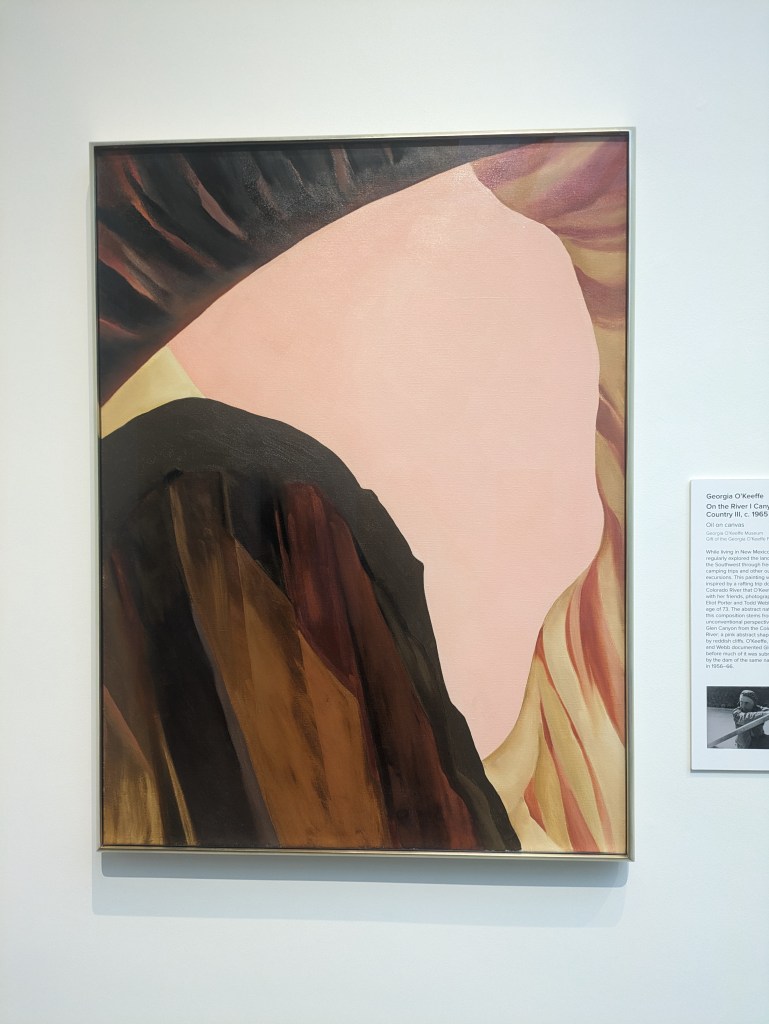

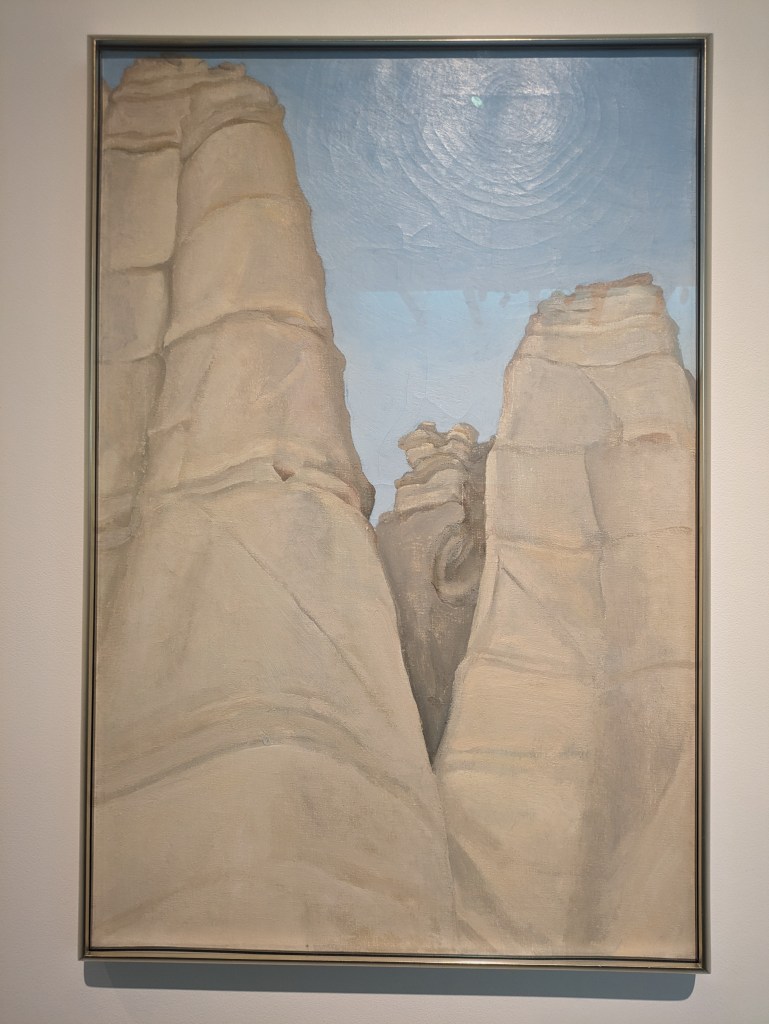

Looking at Georgia’s work is studying an artist’s most sincere testament of love and careful study of the forms and colors of New Mexico. She celebrated the curves of the land as Alfred studied her long neck, elegant hands and shapely facial features.

Her small museum in Santa Fe had roughly six rooms arranged with art that was curated to reflect her ‘periods’. In the first gallery are some works from very early in her life; watercolors from college (above) and some anecdotal photographs and works that showed the beginnings of her development of the aesthetic hallmarks which define her style.

Next was a room with some of her trademark flowers and a five minute film. The film consisted of some interview footage, and a detailed description of her renovating an abandoned adobe house to spend her last few decades in. She seemed cheerful and had even-keeled wisdom about her place in the canon, her philosophies on art making, and her affinity for seclusion and quiet. She wasn’t overly irreverent. Neither was the museum.

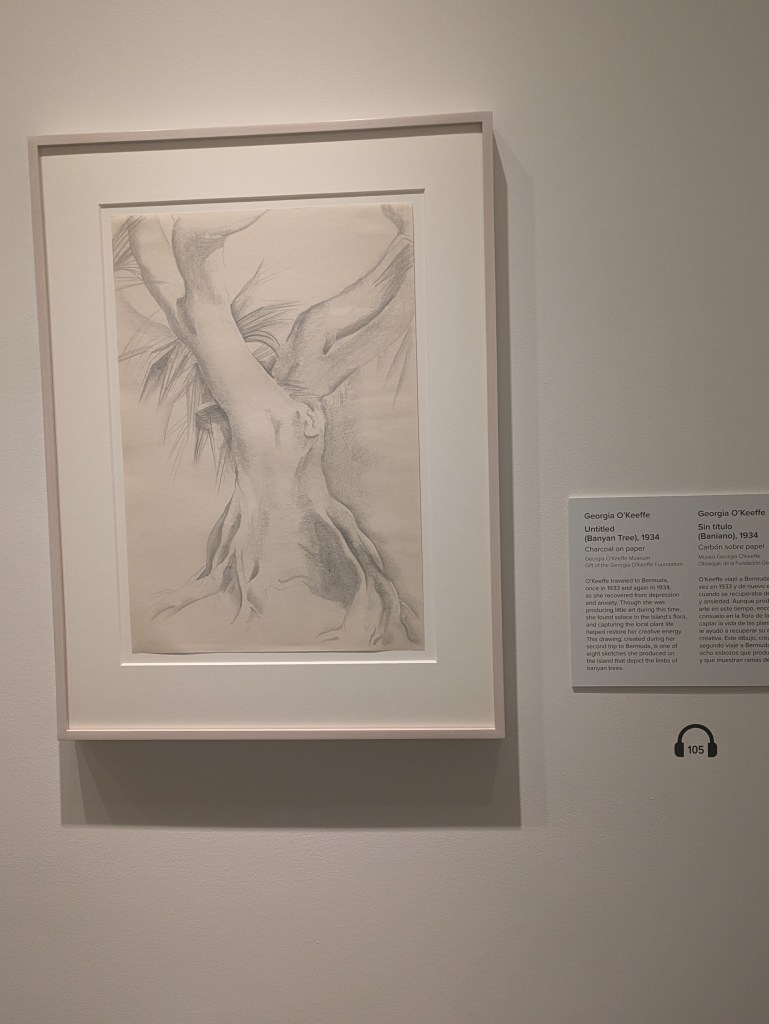

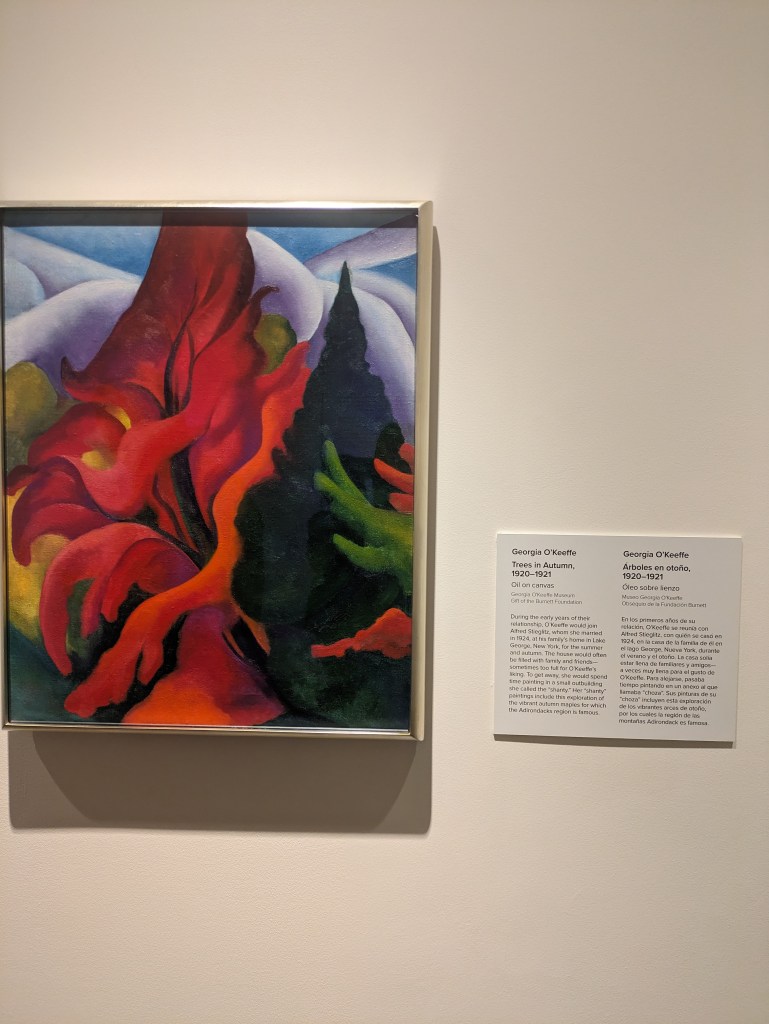

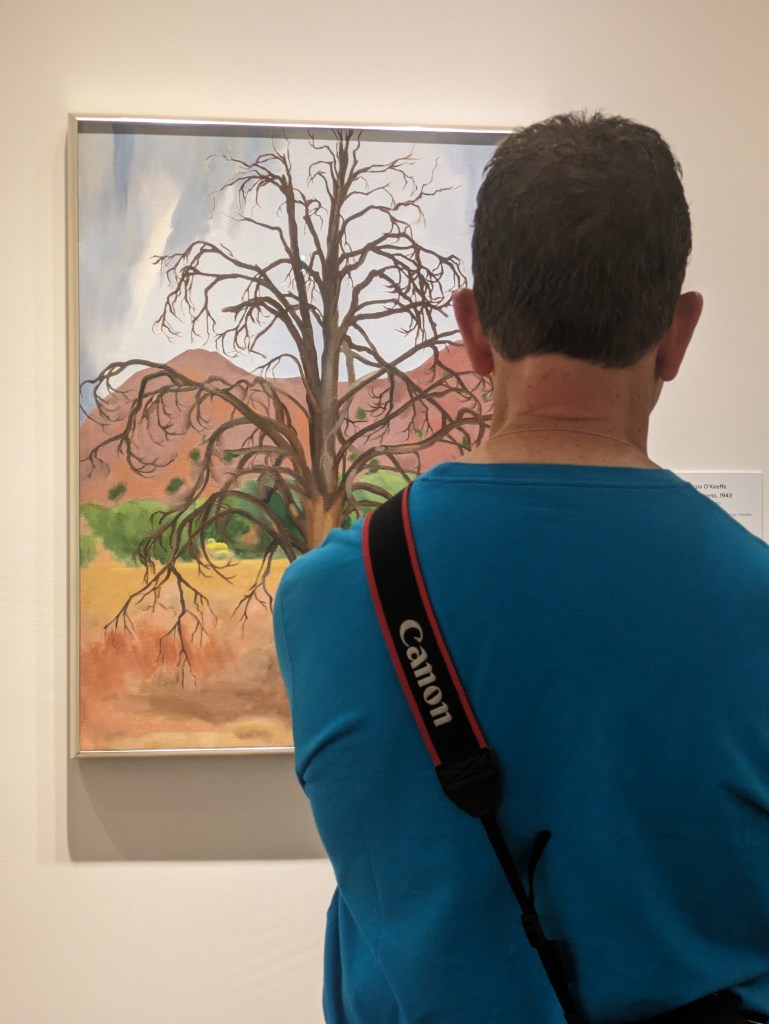

Next was a room dedicated to trees, simple graphite drawings interspersed with oil paintings, and an actual log beside a painting of the log to interpret Georgias translation of objects to paintings, which was fabulous. These trees followed significant changes in her life, from living in oak-tree ridden New England; to finding respite in the baobabs and palms of Bermuda where she spent some time recovering from ‘psychosneurosis’ , to the palms of Hawaii, where she spent time not completing commissions for a pineapple company, and of course some studies of drought stricken, bare stumps surrounding her haunts in the southwest.

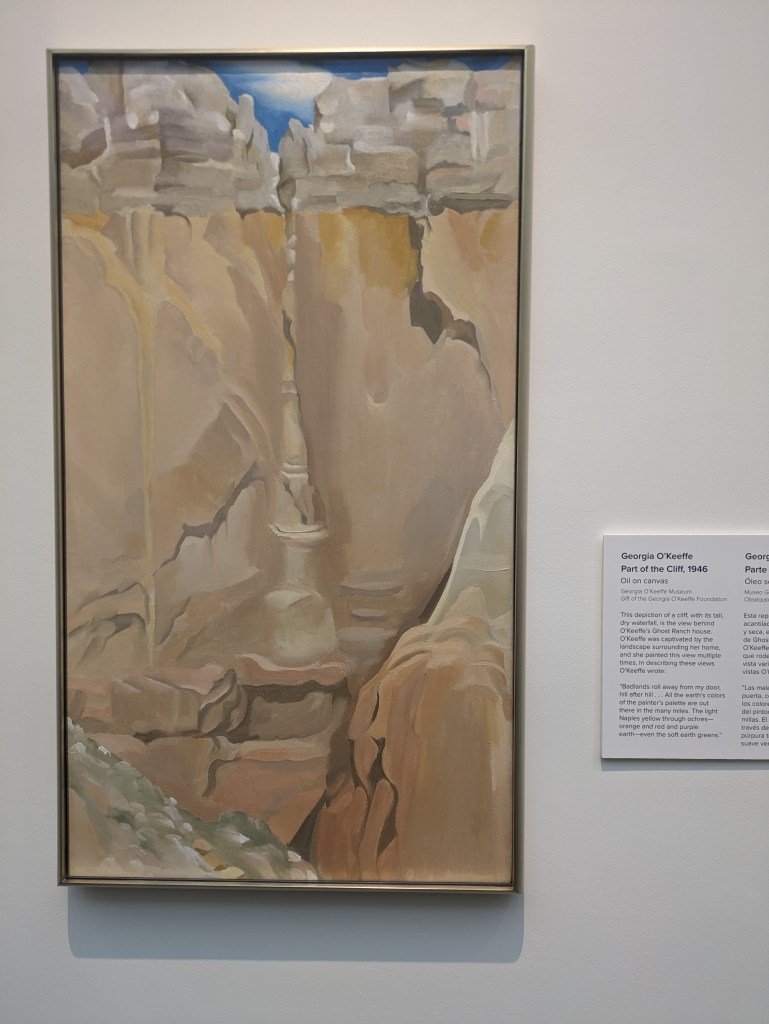

Getting closer to the end of the museum are a spectacular room of her most grandiose paintings; those of rocks, bones, crosses, canyons and mountains she encountered in New Mexico. At the exit were rooms with personal artifacts from her closet, kitchen, and painting studio which illustrated the precision of her dress, her diet, and her studio practice.

So that was my art trip to New Mexico, and if you have ever thought about visiting, don’t ask Georgia O’Keefe in a seance, because she will tell you not to come, while her art beckons you anyway.

Leave a comment